Update on micro-abattoir progress at home and in legislative reform…

These anti-capitalist principles are great, but I still have to pay the rent somehow.

These words have stuck with me since they were uttered by a young would-be farmer last year. They resonated, as, by contrast, I am in a position of undeniable privilege, holding title to unceded Djaara lands, with a well-established and viable livelihood from farming. We are embedded in a community where reciprocity is a way of life and ‘favours’ are remembered rather than recorded on a balance sheet. So what should I say to the 31% of Australians, like the young-would-be farmer, who still have to pay the rent, or to the vanishingly small number who can find a way to stump up a deposit, let alone service a lifetime of mortgage repayments? The cost of land and access to money to buy it is a major impediment to growing more farmers, especially young ones. That is why the Australian Food Sovereignty Alliance (AFSA) established Farming on Other Peoples’ Land (FOOPL) several years ago, to support the emerging movement towards land sharing, and why we are developing an Agrarian Trust to get more people onto land.

Access and affordability of land is here only part of the challenge farmers are facing in the ever-increasing neoliberalisation of agriculture in Australia. With recent development in abattoir closures, we need to also consider those already farming who are losing access to the few remaining abattoirs , who desperately (and urgently) need to build local micro-abattoirs? Surely taking out a loan from the bank is the most expedient and logical pathway? We see trends here with similar challenges that occurred decades ago after the loss of equitable access to dairy and grain processing facilities.

For our purposes here today – to debunk the naturalised assumption that going into debt to get what you want is normal and unavoidable – I am going to talk about why and how to avoid debt to build micro-abattoirs. This is the most pressing issue in the food sovereignty movement in Australia right now. Abattoirs owned by vertically-integrated Australian and multinational corporations steadily bar smallholder from access to slaughter, meaning we are on the cusp of losing small-scale family farms, local butchers, and access to any local meat from animals raised on pasture. (Take these out of rural communities and you also erode the fabric of regional Australia.)

My views on the topic of debt are strongly informed by both our experience of avoiding it here at Jonai Farms while funding major infrastructure projects, and by a lifetime of reading about capitalism and its alternatives, including Indigenous ways of being and thinking, and the rich literatures around diverse economies and degrowth.

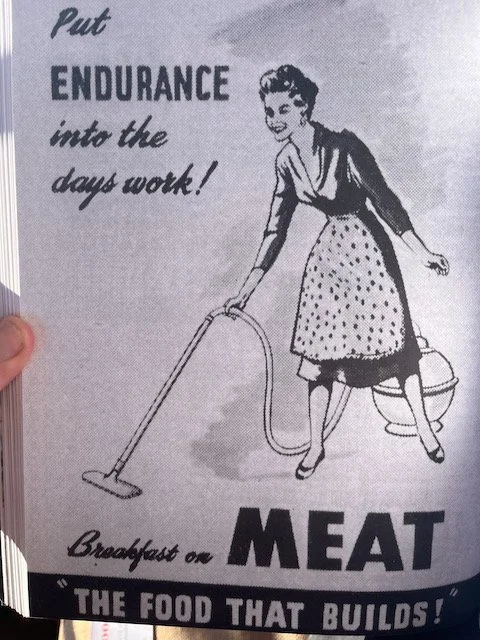

First, let’s unpack the deeply imbued culture of guilt and shame around ‘paying one’s debts,’ which co-exists with a universal despisal of usury – the practice of lending money at unreasonably high interest rates. Who gets to determine what is a ‘reasonable’ interest rate anyway? (Fun fact – usury is illegal in Australia, and the highest legal interest rate is 48% on some unsecured loans! Reasonable?) How did we get to a point where it is reasonable to expect more money back than what you loan somebody? Not so long ago, more people got loans from friends and family than from commercial lenders, but as in so many aspects of modern society nowadays, we transact for more of our needs than we relate for. In fact, going to the bank instead of cousin Dave is now so ingrained in our national psyche that many would never consider asking for help before applying for it, with interest.

Contrast this with a shared belief amongst many First Nations communities here and around the world that we are born in mutual obligation with Land – our mother – and we must meet these obligations to be in good relations with each other. In this world view, our responsibility is ‘to each according to their need, from each according to their ability’ or as we say at Jonai, everyone should contribute and receive ‘commensurate with needs and capacity.’ Nobody is ‘owed’ anything except Country, and nobody has a right to extract more than another can afford to give. Instead, each of us owes the land and the human and more-than-human world care and consideration of their needs. As Tyson Yunkaporta puts it, we are here to look after the land and the sky and everything in between – that’s our niche in the ecosystem. This is in stark contrast to the liberal tradition, which shirks communal responsibility in the narcissistic belief that ‘we don’t owe anyone anything.’

The degrowth movement follows this philosophy about needs and capacity, embracing the notion of how much is enough, celebrating frugal abundance to ensure radical sufficiency for all. ‘Live simply, so that others may simply live’ encapsulates the philosophy well. As Theodore Munger put it in the late 19th century, ‘debt is the secret foe of thrift, as vice and idleness are its open foes.’

Before anybody worries that I’m going to debt-shame people, that is not where this is going. Carrying debt in today’s world is far more common than not – in Australia only 35% of the population has no debt, and the average household debt is a whopping $261,000. The average debt to income ratio (DTI) here is 2:1 – that is, most people owe twice what they earn in a year. This ratio has increased dramatically since the 1970s, and Australia now has one of the highest DTIs in the world. While a longer conversation could be had about why this is so (relatively low interest rates and neoliberal policies that have contributed to the escalating cost of property are central), the key takeaway is that to own property, there are few options other than taking on a hefty bank debt.

But, back to the abattoir issue. What if we step away from prohibitively expensive land costs, and look at something like a micro-abattoir? If you need $150k or $200k to build one, why not take out a bank loan, find some investors, or leverage your existing mortgage? One important reason not to do that is purely pragmatic - because abattoirs are not easily made into profitable enterprises, and even the big ones struggle to service debt on top of operating costs, whether it is accrued from the capital expenditure of the build, or through rent or lease payments. Nearly every small-scale farmer (and other small business owners) knows that while you can forego some expenditures in the lean times, loan repayments are not one of them, or you risk losing everything. So why wouldn’t you try to build a system that is not reliant on debt?

From the pragmatic to the political, let me offer two anecdotes to hopefully de-naturalise our culture’s acceptance of debt.

Say you find some ‘angel investors’ for your project, who only want ownership equity or a relatively low return (apparently 10-20% is considered low in much of that sector, justified they argue because these are usually considered high risk investments). What I see is some wealthy people who are interested enough in your community project to want to support it, but only if they also make some money from it, which is just business as usual. I have never heard of ‘angels’ in the traditional theological sense who need a return for their good work. Having that return on the balance sheet could make the difference between a successful community-controlled facility, or one that is ‘saved’ by said wealthy folks when it cannot service the return, only to be run into the ground by following the old extractive logic of capitalism and trying to extract surplus value from an enterprise that does not generate a surplus.

Now a shorter story. Someone asked me recently if I thought it was okay to charge people rent to help you pay your mortgage, and I said, ‘sure, if they get to keep part of the land too.’ The food sovereignty movement is not seeking to become the rentier class, we are seeking to overturn the rentier class and create a society where everyone has what they need for a dignified life and livelihood. A rentier is someone who earns income from capital without working. Sure, many if not most rentiers work for a living themselves, but grow their wealth not by increasing their productivity, but by extracting the surplus value from the labour of others, who hand over an average of 31% of their income in rent.

One of the principles of emancipatory agroecology is to question and transform structures, not reproduce them. To build the new version of the intrinsic infrastructure of agroecology – collective abattoirs and boning rooms, dairy processing and grain mills – we must be more creative and collaborative than the capitalist system has taught us to be. You can’t borrow your way out of debt, no matter what the masters tell you. Well, not until you are a billionaire I guess, because they say that if you owe the bank 1 million dollars, the bank owns you, but if you owe the bank 100 million dollars, you own the bank. I don’t know about you, but I don’t want to be either of those guys. Another principle of emancipatory agroecology is to cultivate autonomy rather than dependence, and debt quite obviously fosters the latter.

So how do you raise $200k to build a micro-abattoir for a dozen or so local farms?

First, peasants need to pool your change and then figure out how much more you will need. This won’t be done alone: we need to collectivise.

Second, what do you have beyond your current operational revenue and within your human capacity to sell to earn some extra cash? In our case, it has been my cookbook, which I chose to self-publish so that all earnings became part of the Meat Collective @ Jonai fundraiser. (There is a long-running theme here of in-sourcing rather than out-sourcing the work to retain the value ourselves, rather than letting third parties extract it.)

Third, what fundraising events could you host? We partnered with our favourite and most dedicated local restaurant Bar Merenda, and together at a spectacular nose-to-tail feast hosted here on the farm, with loads of support from other farmers, chefs, CSA members, and generally excellent humans, we raised $16,200. The raffle and dinner brought together 15 farms, 16 makers, 10 restaurants, 3 retailers, and a tourism operator, who pooled our collective efforts with a healthy dose of ‘here’s something I prepared earlier’ to deliver an epic prize pool for a raffle, raising a further $39,500! A surprise auction raised another $9,700 on the night.

Rounding all of this out, some of our longstanding (and a few new) supporters and CSA members have donated significant dollars because they see the value to the community and the food sovereignty movement, and they have the capacity to contribute. And back at the beginning of the fundraising, our then-farmhand Adam and a couple of mates had a practice run at raising 10 of our pigs on a nearby property as a learning exercise (handling everything from feed and pig moves in a mobile system to advertising, selling, butchering and delivering the meat), and donated their earnings from the experiment to the future abattoir.

Of course there is also a role for governments in funding the transformation. Matched grants to collective projects can hugely speed up this much-needed revolution. In our case, we had matched funding to build Audrey - our rotating composting drum who is integral to nutrient cycling surplus yield from the abattoir into rich fertiliser for the market garden.

I wrote in an early COVID post in April 2020, ‘Flirting with capitalism while trying to crush it is a dangerous game. Which is not to say that taking on debt makes one a capitalist, but rather entwined in a system that has made it genuinely difficult to make it obsolete.’

I elaborated…

‘But what I will say for the peasants of the world, be we from a long line of people of the land or relatively newly boots on soil is that resourcefulness and frugality are our bedfellows. Unlike our industrial counterparts, most of us eat what we grow, and we grow what we eat. We savour the products of our labour, and we maintain old traditions of preserving for the lean times. These are the hallmark attributes of peasants the world over, and as I have watched my peasant comrades from Australia to Italy, China to the US, South Africa to Brazil, I have seen their self- and community- sufficiency as the world's original preppers have found ourselves prepared.’

I was asked at a talk recently how we re-build trust in a society built on transactions that has lost that communal faith in decency and the common good. My response?

Role model it. If not me, who? If not now, when?

We have been strengthening our trust muscles here for a long time, exercising them through regular trusting (and trustworthy) behaviours.

When another person asked me what return farmers would get if they put money into the abattoir, I said we all get a f*cking abattoir. What more do we need?

With the announcement from Kilcoy (the multinational corporation who purchased Hardwicks abattoir in 2021) that they will no longer take lots of less than 15 cattle or 50 sheep, the urgency of our micro-abattoir project just cranked up. While the Australian Food Sovereignty Alliance (AFSA) is working hard to help farmers secure an extension at least to the middle of next year, and working closely with the government to find ways to make micro-abattoirs easier to develop, it is a very uncertain time for Victorian small-scale livestock farmers.

We have revisited our budget and realise we still need at least another $25k to complete the project. This is because we wasted $25k on consultants who gave us no benefit, and expensive reports required for the permit that could have been avoided if micro-abattoirs were considered ‘rural industry’ - a Section 1 use in the Farming Zone (and Rural Activity, Green Wedge and Green Wedge A Zones) - so no permit required.

In regards to the consultants, we have long eschewed the need for that form of value extraction from our operations, but fell prey to our own lack of confidence that we could design the facility ourselves (in spite of having toured dozens and worked in a few). The fact is, the designer we engaged could not grasp the ‘micro’ nature of the project, and $13,000 later we parted ways with a million dollar useless design. We continued our research, visited and worked in more abattoirs, and designed the facility that Stuart is now about half way through building. (If there are any local boilermakers out there keen to lend a hand for a few days soon, he could use it as he erects the steel frame for the salle de mort and fabricates the rails!)

Our avoidance of consultants is longstanding and underscored by the principles of agroecology, which promote autonomy rather than dependence, and horizontal knowledge sharing built on use value, not just market exchange value of perceived ‘expertise’. Just imagine how much taxpayer money would be available to fund public education and hospitals, dentistry (!), and a Universal Basic Income (UBI) if the government didn’t throw it all at bloated consultancies who cut and paste advice from one expensive report to another to gather dust on yet another public servant’s shelves. Readers may recall the controversies with PWC at the federal level, and the 1200% increase in consulting services in government in the last 10 years, all money which could have directly supported community needs instead.

This is not to suggest that people should not be paid for knowledge hard earned, but how many consultants emerge from their own failed projects or aborted careers in industries they then purport to advise? I think it is worth drawing the distinction too between practitioners and consultants when it comes to a project like a micro-abattoir - you do not need a plumbing consultant - what you need, in fact, is a plumber. Outsourcing expertise to those who have earned their title is different to getting it from those who never held the title.

So back to raising money for the micro-abattoir at Jonai… we will be adding more rewards to our fundraising offer soon, including an option to pre-purchase a limited number of slaughter spots at a slightly higher fee than we anticipate charging on completion to aid with hastening construction.

For $2500, we are also offering a day at the farm for communities working on your own micro-abattoir projects, to walk through the facility, discuss construction, costs, regulations and planning, and hand over all of our paperwork to date (and future paperwork e.g. the abattoir HAACP Food Safety Plan on completion). Legendary Jonai lunch with a side of food politics as always, group size ideally limited to 12 but we are open to negotiation. Contact Tammi to book a date (0422 429 362).

At a spectacular nose-to-tail feast hosted here on the farm in partnership with Pig & Earth Farm, Bar Merenda, and La Pinta on Monday 3 June 2024, with loads of support from other farmers, chefs, CSA members, and generally excellent humans, we raised $16,200. The raffle and dinner brought together 15 farms, 16 makers, 10 restaurants, 3 retailers, and a tourism operator, who pooled our collective efforts with a healthy dose of ‘here’s something I prepared earlier’ to deliver an epic prize pool for the raffle, raising a further $39,500!

As people who have dedicated our lives to food sovereignty and agroecology (Tammi has been president of the Australian Food Sovereignty Alliance (AFSA) for ten years, donating half her time to advocating for everyone’s right to participate in food and agriculture systems), we share everything and practice radical transparency about both our successes and our failures (check out the farm blog for those stories). We have been sharing our documentation in ad hoc ways with other farmers for years, and now are collating them here for anyone to access.

The Meat Collective @ Jonai will serve not only us, but also several other local farms with whom we are in relations, and operate as a not-for-profit solidarity economy on degrowth principles. We are strongly guided by ethics of fairness – central to which is a notion of ‘enoughness’. We talk about each of us receiving and giving mutual aid ‘commensurate with need and capacity’. If sustainability is dealing justly with future generations, it must obviously start NOW with current generations in our dealings with the human and more-than-human world.

In practice, what that means for the abattoir is that fees will be democratically set by all farmer members of the collective to cover costs of operation (energy, compliance, consumables, etc) and ensure all meatsmiths earn a decent livelihood. Critically, no surplus value will be extracted from the system - there are no ‘investors’ and no financial returns beyond the wages earned by those of us doing the labour. The returns are so much more than money, and include beneficial environmental custodianship, highest animal welfare outcomes, and farmer autonomy and well being.

While fundraising for our micro-abattoir to enable the livelihoods of local farmers here in the southern highlands of Djaara Country, we are busy supporting other communities to do the same in communities across Australia, while AFSA is advocating for legislative reform to make it easier to build and operate slaughter facilities such as ours - what Tammi calls the ‘intrinsic infrastructure of agroecology’. You can read about AFSA’s proposed reforms to the Victorian Planning Provisions here.

You can find our successful development applications for both the pig farm and the abattoir on the website, with associated materials such as our environmental management plan (EMP). These documents took a lot of time and knowledge, and some call this Intellectual Property (IP) - but we think protecting that from others’ use or charging a fortune for it is a major barrier to democratic participation and equitable distribution of resources, except in the case of Indigenous Peoples protecting their traditional and cultural knowledge and genetic resources from exploitation by colonial capitalist powers.

Providing financial support for us to build the micro-abattoir will further enable our efforts to radically transform the food system from the ground up. And if you are not in a position to offer any cash to the project, we are grateful for any way you can help spread the word, both for the success of the Meat Collective @ Jonai, and to see more meat collectives emerge across Australia!

For those following the Jonai story since way back when we began in 2011, and our first crowdfunding successes in 2013 and 2014, you will know we are strongly avoidant of debt, and we encourage other communities to look to this model of working collaboratively, spreading the load amongst many, to raise the funds needed to (re)build the intrinsic infrastructure of agroecology.

Help us build a micro-abattoir at Jonai Farms!

Help us raise $50k for the second stage of building a micro-abattoir at Jonai Farms!

Jonai Farms & Meatsmiths and Pig & Earth Farm are part of a vibrant community of small-scale farmers on Djaara Country working to take back control of the infrastructure intrinsic to livestock farming that has been captured by multinational corporations – in this case, abattoirs.

As farmers across the country rapidly lose access to abattoirs, butchers, grain mills and dairy processing, many are working collectively to protect the future of local food against the domination of corporations. Jonai Farms is one of them, collaborating for many years with Pig & Earth Farm in the on-farm boning room built with crowdfunding support back in 2013.

Now it’s time to build the Meat Collective @ Jonai, a micro-abattoir where the Jonai and several other local livestock farmers will be guaranteed the future of slaughter with the highest animal welfare. Without more of these facilities all around Victoria and Australia, local communities are about to lose access to local meat, as ever-fewer multinationals consolidate ownership of abattoirs into ever-fewer hands keen on export rather than feeding locals.

FUNDRAISER DINNER AT JONAI FARM 3 JUNE 2024

You can lend your support and reward your palate with a delicious four-course meal of local produce prepared by our ethicurean friends at Bar Merenda, with help from the equally community-minded Adam Racina of La Pinta seriously-good-food notoriety. Beer, cider and wines all from comrades across the region will ensure libations will be as delectable and full of integrity as the food. All produce for the dinner has been donated by Jonai, Pig & Earth, Tumpinyeri, Mt Franklin and more…

All of the beverages for the evening have been kindly donated by our friends Love Shack Brewing, Maidenii Vermouth, Lapalus Wines, Minim Wines, Defialy Wines, Joshua Cooper Wines, Syrahmi, Bindi, LattaVino, Musk Lane, A&C Ainsworth, Dilworth & Allain, North Wine.

We have raised over $50k to date towards the $150k build. We aim to raise another $50k on the night between ticket sales and a raffle run hybridly in person and online on the night, with prizes ranging from packs of local pastured meats, mixed dozens of artisanal wines, and more…

To reach our target, we are offering the night at a minimum dinner price of $250 – all food and drink included – with a ‘pay what you feel/can’ option to contribute more. The evening will commence with a farm tour at Jonai to see what has been achieved in the first 12 years, and plans for the next 50!

You can also buy a raffle ticket for an amazing list of prizes, and you don’t even have to be at the dinner to win!

Link to abattoir updates elsewhere on the website, including ongoing fundraiser with Tammi’s forthcoming cookbook – Eat like the Jonai: Ethical, ecologically sound, socially just & uncommonly delicious!

WE WON! We can FINALLY start building an abattoir at Jonai Farms & Meatsmiths!

Winning the battle against the erosion of the Farming Zone

On Tuesday the 5th of March, we received the VCAT orders that uphold Council's decision to grant us a permit. The VCAT ruling affirms our position that abattoirs are intrinsic to livestock farming, and recognises that smallholders are losing access to the large abattoirs at an alarming rate.

Perhaps most importantly, a strong precedent has been set that small-scale abattoirs are an appropriate land use in the Farming Zone, and we Jonai are very hopeful of seeing many more flourish in the years to come!

In her orders, Senior Member Naylor wrote:

In light of the lack of any clear planning policy discouraging an abattoir in the Farming Zone; the ability for a permit to be granted for an abattoir; the small scale nature of this proposed abattoir (rural industry); and, for reasons that I will explain next, the lack of any material to indicate that this small scale rural industry will produce unacceptable amenity impacts, I am persuaded that it is appropriate to grant a permit for the proposed abattoir in the Beacon Paddock part of this site.

The objectors tried to claim that there is nothing inherently agricultural about an abattoir (seriously?!), and that we were trying to pull a swift one and turn our farm into an industrial use. Never mind that most of them are lifestylers on some of the highest quality agricultural land who have removed their land from farming, contributing to astronomical land prices that make it nearly impossible for young farmers to take up farming. In stark contrast, we made the decision over a year ago to open our farm to Tumpinyeri Growers in a rent-free landsharing arrangement so that they can earn a livelihood from market gardening. A great irony was that the lifestylers made this fruitless argument in the same week that I had a PhD article published entitled 'Building the intrinsic infrastructure of agroecology: collectivising to deal with the problem of the state'.

The senior member’s ruling states:

There is nothing in the agricultural or industrial land use policies that discourage an abattoir land use from being located in a Farming Zone. Mr O’Neill & others have submitted this is an industrial land use on farming land with no intrinsic link to agriculture. I am not persuaded of this submission in regard to this proposal. ‘Intrinsic’ is defined in the online Macquarie Dictionary as an adjective meaning ‘belonging to a thing by its very nature’. I agree with Mrs Jonas’ submission that it is inherent in farming that livestock is grown for consumption (amongst other purposes), so the slaughtering of livestock does belong by its very nature to the growing of livestock. Mrs Jonas points out farmers can legitimately slaughter their own livestock for their own consumption on their farms. An abattoir is then a place in which livestock can be slaughtered for a larger cohort of consumers. How large a scale this may be depends upon the characteristics of the particular abattoir. In this proposal, Mrs Jonas is referring to it as a micro abattoir.

484 days elapsed between lodging our development application and VCAT handing down its decision, during which time we witnessed another abattoir (Castle Estate) cease processing beef and lamb, affecting as many as 1000 smallholders according to the Weekly Times, and the red meat abattoir we use has reduced smallholder access yet again.

We could have built the abattoir in those 484 days and be up and running, ensuring the resilience and livelihood of our own and another dozen farms, if there was one simple amendment to the planning scheme to exempt very small abattoirs from requiring a planning permit. I detail the proposed reform below, but first, let us share our immediate plans after our success at VCAT and in consultation with Primesafe, Victoria’s meat industry regulator, who have been very helpful and supportive as we have progressed.

What’s next: a vehicle-based abattoir

Early this week a 40-foot refrigerated container will be delivered for Stuart to commence conversion to a vehicle-based abattoir, which will be a smaller facility than originally planned, but still sufficient for our and several others’ needs. An amendment to the Meat Industry Act in 2021 made vehicle-based abattoirs a legal option for slaughter for commercial sale of the meat, thanks to the lobbying efforts of Provenir, the first licensed mobile abattoir in Victoria. Although we finally won our battle for the planning permit for a fixed facility, which grants us land use permission, a vehicle-based option does not require one, and nor does it require a building permit. This makes the build much more streamlined and affordable than a fixed facility, and a container is something Stuart is skilled to convert himself with minimal need for contractors (the existing boning room and commercial kitchen are containers Stuart converted a decade ago, both of which are considered Rural Industry under the planning scheme and exempt from permit requirements in the Farming Zone).

The decision to shift to a vehicle-based abattoir was strongly influenced by the ever-increasing uncertainty of the security of our current slaughter options, and commences what will be a staged approach. We envision building the fixed facility within the two years we have to activate that planning permit. We are simply worried we are running out of time, and need a facility urgently. In fact, smallholders across Victoria and the rest of the country need these solutions urgently, and we hope ours will serve as a blueprint for others. Below I outline the simple reform that would enable others to build small facilities in the Farming Zone – intrinsic to the future of small-scale livestock farming.

We will, as always, share details of the plans and progress via social media – check out our new Instagram account @meatcollective_jonai if you want to follow along!

We will crank up the fundraising now that we have certainty, but are delighted at the lower cost of a container conversion, so only looking to raise up to $150k instead of over $400k – a much more readily achievable target. To date, we have raised $48,250 and spent $33,345. Unfortunately, some of that spend was wasted on consultants we could have avoided if we had not required a planning permit, with about $11k being useful for either option and $22k not so much. So realistically, we still need to raise around $140k, but will also continue to use monthly surplus from the business to fund it at the speed of our bank balance.

Jump onto the website to support the project and keep up with our progress.

The need for reform is urgent – micro-abattoirs are rural industry

A report by a parliamentary inquiry on animal welfare in the UK has outlined the challenges farmers face without access to local processing facilities and extensive benefits to small-scale farmers, animal welfare, and environmental outcomes from supporting the development of small-scale abattoirs. The issues and benefits are also highly applicable to the Australian context.

The Canadian province of British Columbia also introduced legislation in 2021 to ease the burden on small-scale livestock producers who slaughter small numbers of animals on farm for sale off farm. The legislation allows on-farm slaughter of small numbers of animals for direct sales locally, and custom slaughter of other farmers’ animals with a slightly higher level of scrutiny.

In Victoria, ‘rural industry’ is an acceptable use in the Farming Zone, and is what enabled us to run a boning room for the past decade without a planning permit. However, the scheme specifically excludes abattoirs and sawmills[1], requiring them to be permitted. The Australian Food Sovereignty Alliance has long proposed a very simple change to the legislation to enable on-farm micro-abattoirs with a low throughput of animals.

Recommendation

Amend the Victorian Planning Provisions to reduce regulatory burden on small-scale abattoirs in the Farming Zone commensurate with the low risk they pose to environment and amenity.

First, include a definition for ‘micro-abattoir’ in the Meat Industry Act, defined as an abattoir processing fewer than 1000 Livestock Units (LSU) per annum, and/or generating less than 200 tonnes of organic waste, processed and retained on farm according to EPA Guidelines.[2]

Second, include micro-abattoirs as a Section 1 use (no permit required) in the Farming Zone under Rural Industry, as distinct from large, industrial abattoirs, and in alignment with EPA Guidelines.

[1] AFSA also supports a concurrent change to enable small-scale sawmills, as the use of small, portable mills (e.g. Lucas mills) for sustainable agroforestry is already quite widespread, and should be allowed without a permit to support diverse business models, as is common on agroecology-oriented farms.

[2] EPA Victoria publication 1588.1 Designing, constructing and operating composting facilities. As the organic surplus yield has been generated and retained on site, a works approval and licensing are not required.

Below is what we have submitted in response to objections to our proposed micro-abattoir at Jonai Farms:

9 March 2023

Re: PLN22/0346 – Development Application for a micro-abattoir at Jonai Farms & Meatsmiths (Dja Dja Wurrung Country, 129 Morgantis Rd Eganstown VIC 3461)

To Hepburn Shire & those who have raised objections:

Farmers globally have seen the closure of local abattoirs over several decades, bringing longer travel times for livestock and farmers, and difficulties finding a facility that meets farmers’ slaughter schedule, let alone values. Many of the large, industrial abattoirs have refused service for small-scale farmers entirely, leaving them with no option except to stop farming.

Here at Jonai Farms, we have experienced the acquisition of both abattoirs we use by multinational corporations in the past couple of years, and decreased access since. JBS, the largest meatpacker in the world, bought the abattoir where we slaughter pigs last year, and almost immediately reduced the days on which we can access slaughter. (This huge global corporation has been involved in a long list of scandals, including serious breaches of animal welfare and work safety. See the Four Corners story we contributed to – The Butchers from Brazil - to learn more about what we are facing.)

In response to diminishing access and increasing risk to our livelihood, we have been actively investigating models for local abattoirs since 2017, and concluded that building a micro-abattoir on our farm to service a small group of local farms is the best solution. Small-scale abattoirs on farms can provide far greater welfare outcomes for animals – shorter or no travel distances/times, less stress, and smaller holding facilities, and positive outcomes are greatest where there is more farmer control and participation in decision making. Unlike their industrial counterparts, small, local abattoirs are embedded in communities – the connection to neighbours and ecosystems are a built-in risk mitigation measure as they are answerable to their communities in a way massive facilities behind locked gates will never be. The viability of a local abattoir is also greatest when there is no lease payable to a landlord, given the very small margins of most abattoirs.

The objective of the Jonai Meatsmith Collective abattoir is to effectively and safely construct and operate a micro-abattoir on our agroecological farm for best practice animal welfare outcomes in a way that addresses climate change and biodiversity loss through avoided greenhouse gas emissions and a circular bioeconomy. The facility will have capacity for no more than 15 farms over the course of a year, who process between one and 14 animals per month. The maximum number of animals on a slaughter day is 30 pigs or 6 cattle. We detail a typical slaughter day below. Slaughter will take place no more than one day per week, as we are primarily a farm, not an abattoir, where slaughter is an ancillary and necessary part of farming livestock. We are fundamentally committed to protecting the environment and amenity of our neighbours, ourselves, and communities downstream – everything we do here has demonstrated that commitment for nearly 12 years.

We understand that for many people the idea of an abattoir – a slaughterhouse – evokes fear and even ‘disgust’ (as one objector wrote). We believe that this is a result of our disconnected food system, where people have grown so accustomed to buying plastic shrink-wrapped meat on polystyrene trays from one of the two supermarkets that control over 70% of retail food sales in Australia that they forget – or prefer not to think about – the fact that animals are raised and killed somewhere so that you can eat meat.

We are most disappointed by the objections advocating for animals to be transported longer distances to industrial zones for slaughter, rather than in the farming zone where they are raised.

Just because the industrial food system is currently the ‘norm’ in Australia doesn’t mean it should be, nor does it have to be. What is normal about raising genetically uniform sheds of pigs and poultry, or feedlots of cattle munching grain, which concentrate effluent and create enormous risks to environment, amenity, and public health?

Industrial intensive livestock systems are creating what evolutionary epidemiologist Rob Wallace calls 'food for flu’ – they are the source of most emergent novel viruses that pass from animals to humans. And those are the animals in the abattoirs we have had no choice but to use since we started farming in 2011 – abattoirs that we are losing access to as outlined above.

Essentially, that industrial system is what objectors are advocating for by objecting to small-scale local facilities. Objecting to small-scale localised food production, processing and distribution supports the current ‘norm’ of intensive industrial livestock production as the ‘standard’, condemning millions of animals to lives of misery and stressful transport on their last day, and undermining the efforts of small-scale livestock farmers embedded in local communities.

Before we address specific objections, let us walk you through what the abattoir here will really look, smell, and sound like. Note firstly that we are in the Farming Zone, in which abattoirs are a Section 2 use as ‘rural industry’; a ‘permitted use’ subject to being granted a permit. Boning rooms, dairy processing, and other forms of rural industry are allowed with no permit. Rural industry and animal sounds are both a normal part of farming, and as farming is an ‘as of right use’ of the Farming Zone, they are protected from lifestyle complaints unless they are deemed excessive by ‘reasonable persons’.

A Typical Day in the Jonai Meatsmith Collective Abattoir

At 7:30am on a Monday, we will walk 10 pigs along our internal farm road from their paddocks to the abattoir yards. One animal at a time is separated from the others using boards, and then slowly walked around a curved chute with solid walls (to prevent animals from seeing unusual light or strange animals, which can cause stress[1]) and a non-slip floor to the knock box (a small crush that holds animals firmly in place, which has a calming effect according to leading animal welfare scientist Temple Grandin).

Once secure, the slaughterperson stuns the pig with a captive bolt gun, which makes a sound that does not carry more than 50 metres (the nearest house is 200 metres away). The pig is rendered unconscious and is rolled to the side into the facility, where it is bled, causing it to die immediately. Dehairing and evisceration are conducted inside the facility before another pig enters the knock box. By 10:30am, all of our pigs are slaughtered and in the chiller.

During the processing of our animals, two farmers have arrived with their pigs, one driving a Mitsubishi Triton and pulling a 10 x 5 foot tandem trailer with eight pigs, and the other a Ford Courier pulling a 6 x 4 single-axle with four pigs. The farmers unload the animals with assistance from the on-site stock manager into separate holding pens with solid walls. They have access to water and are under shelter. Any vocalising is unlikely to be different from that of the normal sound of animals on a farm.

Animals are held for approximately two hours before slaughter so that they settle from the stress of transport. They are then slaughtered one by one in the same manner as our pigs before them.

Processing is finished by 3:30pm, after which we clean the facility. At most, the facility will use 1500L of water in a day. To put this in context, the average household uses 900L per day, and a household of five typically uses about 1500L – the same as the abattoir. The septic system, like thousands of them around here and across Australia, is well equipped to cope with the small volume of wastewater.

The next day, further processing will commence, and a mostly on-farm resident team will break carcasses down into a range of fresh cuts, smallgoods, and charcuterie, just as we have done for nine years. Farmers will collect their packaged meat as they have done for several years to sell through their own CSA memberships and farmers’ markets, supplying around 1000 local and Melbourne households with highest welfare meat from animals raised in healthy agro-ecosystems.

A waste-nothing approach will ensure that there is minimal surplus nutrient, as most by-product will be further processed for human consumption (e.g. blood and offal) or hides or leather. While most bones are delivered to CSA members to make stock at home, any surplus bones, as well as stomachs and their contents, and other surplus yield from processing will be composted in our in-vessel rotating composting drum – affectionately known as Audrey – just as they have been for the past two years. This creates a rich compost for the market gardens of Tumpinyeri Growers farming here with us adjacent to the abattoir, thereby promoting improved water retention, ground cover, carbon sequestration, and biodiversity while supporting young farmers’ access to land. In a time of escalating crises of climate change and biodiversity loss, we are offering a viable and beneficial solution for resilience – a genuine circular economy right here on the farm.

We have made soap from surplus fat for nine years in 15-30L batches, and can assure everyone that there is no offensive smell, such as there might be at a big industrial rendering plant.

The Collective’s energy requirements for electricity and hot water will be managed with renewables to minimise greenhouse gas emissions. Water will be collected from the roof of the facility and stored in a 100,000L tank. A new bore has been drilled to supply water to Tumpinyeri’s acre of commercial garden beds, which provides a backup to rainwater storage in the case of multiple years of drought (we have applied for a licence for up to 4ML per annum).

The Hepburn Shire Community Vision and Council Plan aim for ‘a resilient, sustainable and protected environment,’ ‘a healthy, supported, and empowered community,’ and ‘diverse economy and opportunities.’ The Collective will be a localized, ecologically-sound, and socially-just operation supporting up to 15 local farms, and employing at least five FTE workers across its direct and ancillary activities. It will bring value chain control into the hands of more farmers, providing a more resilient local agricultural sector. It also meets the Shire’s ambitions to be an ecologically-sound and socially-just agri-tourism destination, with flow-on benefits to the other farms with farm gate shops.

Jonai Farms Responses to Objections

Objection: The proposed site is next to waterways feeding Deep Creek Spring

Objection: The safety of our drinking water is at risk from contamination.

We firmly believe that all of us must be good stewards of land and water, and understand how water flows to and from the lands in our care.

Schedule 1 (ESO1) states that: “Hepburn Shire is situated in the Central Highlands at the source of a number of catchments linked to Port Phillip Bay or the Murray River. Protection of the quality of this water has significant local and regional implications, especially where these catchments provide domestic water supply.” Our farm, like all properties in this area, is in a Special Water Supply Catchment, which is why there is an Environmental Significance Overlay (ESO) applied to properties across the central highlands.

As a pastured pig and cattle farm, we already exclude animals from waterways, and have planted vegetated filter strips above dams and on sloped areas where water flows in high rainfall periods. We keep stocking levels in balance with the ecosystem so as not to produce excess nutrient, and have never applied synthetic fertiliser.

As the primary objective of the ESO1 is to protect the quality of local waterways, the relevance to the abattoir is to ensure separation and filtration between the facility and any solid or liquid waste and two seasonal waterways: one that runs directly behind a dam in our pig paddocks and one that commences on Morgantis Road.

We propose to site the abattoir approximately 175m from the seasonal waterway on Morgantis Road (well in excess of the 30m buffer required by Clause 14.02-1S see site plan below). We have started to develop a silvi-agriculture system in the paddocks below the abattoir site already, which will host hundreds of diverse trees and shrubs in rows 25 metres apart (between which Tumpinyeri Growers are setting up their market garden beds). We chose to develop this system as part of our ongoing commitment to revegetating the landscape for health and beauty, increasing the biodiversity richness to improve ecosystem function by welcoming a broader diversity of species from soil fungi to native grasses to small birds, frogs, and micro-bats. The increased vegetation will also serve as an extra layer of filtration between the abattoir and the waterway. There is also an existing shelterbelt of oaks, blackwoods and wattles we planted nearly 10 years ago along Morgantis Road.

The North Central Catchment Management Authority (NCCMA) has reviewed the application and has ‘no objections’.

While we have long demonstrated care for the water catchment area, we note that there are no controls on chemical application in the Special Water Supply Catchment, and it is unknown how much fertiliser, pesticide, herbicide and fungicide runoff enters the water supply. Guidance from the health department simply recommends that farmers ‘prevent stock access’ to waterways, ‘use and manage nutrients wisely’ and ‘optimise agricultural chemical use’ in catchment areas[2]. Our farming practices evidence much higher ambitions than this.

Objection: Effluent from the slaughter process will be pumped to surrounding paddocks.

Effluent from the slaughter process will not be pumped onto surrounding paddocks. The miniscule volume of wastewater (that may contain wash down water, small volumes of blood, stomach contents, manure, or environmentally-sensitive cleaning liquids) will be captured in sub-surface irrigation and a septic tank. According to the land capability assessment by a qualified earth scientist, which scopes the land capability for higher use than planned:

‘The land application areas have been determined for the 9th decile wet year and satisfies the requirements of Environment Protection Regulations 2021 in that the effluent disposal systems cannot have any detrimental impact on the beneficial use of surface waters or groundwater.’

Our Environmental Management Plan (EMP) submitted to Council states:

Lairage [a.k.a. holding yards] has been designed according to Temple Grandin’s world-renowned high animal welfare designs. Effluent is washed into a holding tank, to be collected and spread on paddocks, as per Livestock Disease Control Act 1994, and EPA Publication IWRG641.1 Farm waste management.

Given the small number of animals in the holding pen on a slaughter day, this practice is the equivalent of the manure from animals grazing in a paddock on any given day being spread on a paddock to ensure it doesn’t concentrate in the yards.

Note that many local farms regularly apply fertiliser to their paddocks (in the form of raw chicken manure or synthetic nitrogen) far in excess of the small additional manure the abattoir will create through bringing in 5-20 external animals one day per week to be held for two hours in the yards.

Objection: Animal waste products will be disposed of on the property.

The abattoir will have equipment and space to ensure we can save cattle hides and edible offal for member farms, and to process intestines for sausage casings (as per AS 5011:2001). Blood will also be collected in a hygienic manner for human consumption in accordance with AS 4696:2007. This significantly reduces the volume of liquid and solid surplus nutrient for composting on site. ‘Waste’ management will be in accordance with PrimeSafe standards and relevant environmental regulation and guidance, where all waste is contained, treated and re-used on site.

All surplus nutrient will be combined with locally sourced carbon material (wood chips/sawdust and soiled cardboard). All on-farm composting occurs via in-vessel rotating drum, reaching a minimum of 55C for three days, managed in accordance with EPA guidelines and AS4454-1004. On rare occasions where composting is not suitable, surplus yield (liquid and solid) will be removed, managed, and disposed off-site to an approved rendering plant for further processing. The composted material is stored in IBCs to mature for a minimum of three months before later spreading on pasture and garden beds. Re-use of composted material is subject to soil testing and agronomic advice to ensure nutrient uptake by actively growing plants.

The solid inedible material generated per day of operation for beef is maximum 750kg[3], of which approximately 100 to 200 kg (hides) is removed from the farm for tanning, and approximately 640kg to be managed on farm. All material that is designated for tanning or rendering off-site is stored in covered bins typically until the morning after processing, and for no more than 50 hours; it is then transported directly to the tanning facility in Ballarat or a relevant rendering facility.

The solid inedible material generated per day of operation for pigs is maximum 420kg to be managed on farm.

The material managed on farm can include paunch contents, rumens, condemned tissues, and meat and fat trim. If the capacity of the on-farm surplus yield management system is insufficient to manage the material, the Collective will remove these from the farm to an approved rendering plant.

Objection: Animal transport vehicles will deteriorate an already fragile road and make dust and noise problems worse.

The abattoir is so small it will only operate at its full potential one day per week, and the farm utes who bring between 1 and 10 animals on the single slaughter day per week are small (e.g. the biggest might be a Land Cruiser pulling a 10 x 5 foot tandem trailer). There will be approximately one to three such vehicles on a slaughter day (2-4 times per month depending on the local farmers’ slaughter schedules – many do not slaughter every month).

For comparison, we regularly see much larger trucks travel Morgantis Road to properties north of us, including weekly Woolies delivery trucks and municipal waste collection trucks. Some of the lifestyle blocks on our road have recently had as many as two dozen large dump trucks with tipper trailers driving loaded up and empty down Morgantis Road for landscaping purposes several days in a row.

The facility will in fact eliminate the heavy trucks that have delivered carcasses back from the big abattoirs to our boning room for the past nine years (approximately three per month historically).

Objection: Flies, noise, and offensive odours go hand-in-hand with abattoirs.

First, we remind Council and objectors once again that ‘Abattoir’ is a Section 2 use in the Farming Zone Clause 35.07. That is, abattoirs are considered ‘rural industry’ in the planning provisions, but unlike boning rooms or dairy processing facilities, they require a permit to operate. To address Clause 35.07-6 Decision Guidelines, we have submitted an Environmental Management Plan to demonstrate the ways we will meet our responsibilities.

While abattoirs meet the aims and requirements of the Farming Zone, we know that some abattoirs (and farms) can sometimes produce noise, odours, and flies that may be objectionable or affect the amenity of neighbours. We value an aesthetically and aromatically pleasing farm, and all measures are in place to reduce potential fly breeding grounds (e.g. closed containers for the small amount of waste before it is composted). The tiny number of animals slaughtered with the highest welfare standards mean noise and odour should not be any different to a normal farm with livestock manure and normal life sounds. We want our animals and those of us who live and farm here to have a pleasant place to live.

Objection: The abattoir site is amongst a group of six (6) residential homes.

Sited in the Farming Zone (not a Residential Zone), our own home on the farm is the closest to the proposed site at approximately 50 metres away, and the other closest adjacent homes are 200 and 250m respectively. As we easily meet the separation distances required from dwellings on another property, and are in the Farming Zone, we consider this objection irrelevant.

Objection: Local properties will decrease in value

While we appreciate that property values might be adversely affected by the construction of a large-scale abattoir at the proposed site, this is not what is proposed. Details above clearly demonstrate that the facility will have negligible impact on roads, and none on water quality or neighbours’ amenity. The structure will be attractive and surrounded by market gardens and rows of diverse trees and shrubs. With its biodiversity and economic diversification, our farm is what the UN Food & Agriculture Organisation calls an ‘Agroecology Lighthouse’[4].

Jonai Farms has been featured in a number of beautiful cookbooks, on multiple shows on the ABC (including Landline and Four Corners), on Channel 10’s The Project and Channel 9’s The Living Room, and most recently on Down to Earth with Zac Efron on Netflix. We genuinely believe that we are a farming community showing the way to a liveable and joyful future, who attract more people to the region because they see the greater resilience that systems like ours provide in the face of climate change and more pandemics.

Objection: An abattoir will deter tourists who stay in local short-term accommodation.

While the objectives of the Farming Zone are not to support tourism, Hepburn Shire is a well-known tourist destination. We note that the position of objectors who want more tourists in Eganstown, which means more traffic, is in direct contradiction to concerns about increased traffic.

However, we don’t believe the minimal increased traffic due to the growing number of short-term accommodation options in the area warrants community concern. These tourists have visited our farm gate shop for many years as well, and will continue to do so when we have a new shop next to the abattoir. In fact, our popular range of agri-tourism workshops draw domestic and international tourists to the area, and their need for short-term accommodation is obviously synergistic with those who provide it.

Objection: Expert advice funded by government warns against an abattoir on this type of site.

This is a vexatious objection with no evidence to support it. It was printed on a flyer distributed in our area with an email address provided for residents to make further enquiries. When another local emailed the party, the response was as per the screenshot below:

‘Abattoir’ is a Section 2 use in the Farming Zone Clause 35.07. Not only does the Land Capability Assessment (LCA) cited above clearly demonstrate that the land is suitable for the purpose of a micro-abattoir, which thus also meets the Decision Guidelines, there are many policy frameworks and strategies at all levels of government that support the development as per below:

The Hepburn Planning Policy Framework[5] Clause 14 Natural Resource Management states that ‘Planning should ensure agricultural land is managed sustainably, while acknowledging the economic importance of agricultural production.’

The Hepburn Planning Scheme[6] aims include:

02.03-4, Agricultural land: Emerging rural industries include locally sourced produce, value added food manufacturing and related products and rural tourism

02.03-7, Rural enterprises: Hepburn Shire is a significant agricultural region and part of Melbourne’s‘ food bowl’. The region’s contribution will become of even greater importance to the State in adapting to a changing climate.

14.01-2S, Sustainable agricultural land use, strategies: Encourage diversification and value-adding of agriculture through effective agricultural production and processing, rural industry and farm-related retailing.

17.01-1S, To strengthen and diversify the economy: Improve access to jobs closer to where people live.

19.01-1S, Support energy infrastructure projects in locations that minimise land use conflicts and that take advantage of existing resources and infrastructure networks. Facilitate energy infrastructure projects that help diversify local economies and improve sustainability and social outcomes.

The Farming Zone Decision Guidelines[7] state:

The need to protect and enhance the biodiversity of the area, including the retention of vegetation and faunal habitat and the need to revegetate land including riparian buffers along waterways, gullies, ridgelines, property boundaries and saline discharge and recharge area.

We plan to plant a diverse range of trees and shrubs in concentric arcs from just beyond the facility to Morgantis Road, creating a silvi-agriculture system for holistically grazing livestock, growing grain, and a market garden. The plantings will create several benefits through increased biodiversity, habitat, shade, fodder, improved soil health, and to beautify the paddock from the perspective of Morgantis Road.

Hepburn Z-NET[8] is a collaborative partnership bringing together community groups, organisations, experts and council to shift the Hepburn Shire to zero-net energy by 2025 and zero-net emissions by 2030. As the only local slaughter facility, the Collective will significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions with drastically shorter driving times for several farms, with the important additional benefit of less stress for animals transported shorter distances to slaughter (or in the case of our animals, not transported at all). The facility will be on standalone solar and use waste vegie oil to heat water, creating a further significant reduction in fossil fuel reliance.

The Sustainable Hepburn Strategy[9] advocates themes for ‘beyond zero emissions,’ ‘biodiversity and natural environment,’ ‘low waste,’ and ‘climate resilience,’, all of which the Collective’s development will promote and progress.

Alignment with Victorian Policy

Victoria’s new 10-year Strategy for Agriculture[10] emphasises building resilience including to our changing climate. It is structured around the following [relevant] themes:

Recover from the impacts of drought, bushfires and the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and become an engine of growth for the rest of the economy. Including a commitment to: Support farmers with information and tools to build resilience.

Protect and enhance the future of agriculture by ensuring it is well-placed to respond to climate change, pests, weeds, disease and increased resource scarcity. Including a commitment to: Ensure Victorian agriculture is well placed to manage climate risk and continues to be productive and profitable under a changed climate.

The Victorian Animal Welfare Action Plan’s[11] vision is for ‘A Victoria that fosters the caring and respectful treatment of animals.’ It has explicit aims to ensure that ‘the market has confidence in Victoria for ethical and responsible animal production.’ Jonai Farms and our Collective member farms put animal welfare first in all production choices – all livestock are pasture-raised on grass and enjoy the ‘five freedoms of animal welfare’:

Freedom from hunger and thirst: by ready access to fresh water and a diet to maintain full health and vigour.

Freedom from discomfort: by providing an appropriate environment including shelter and a comfortable resting area.

Freedom from pain, injury or disease: by prevention through rapid diagnosis and treatment.

Freedom to express normal behaviour: by providing sufficient space, proper facilities and company of the animal’s own kind.

Freedom from fear and distress: by ensuring conditions and treatment which avoid mental suffering.

The Collective Abattoir will strengthen all farms’ capacity to ensure animals are free from the discomfort of long transport and waiting times at distant abattoirs, and from the fear and distress associated with those activities and environments.

The North Central Victoria Regional Sustainable Agriculture Strategy[12] is a high level strategy that suggests moving towards greater adoption of sustainable agriculture that will require land managers to collectively reconsider current practices.

The North Central Regional Catchment Strategy[13] priority directions include: ‘Continue to increase the uptake of sustainable agricultural practices through implementation of the Regional Sustainable Agriculture Strategy, Soil Health Action Plan and Land and Water Management Plan for the Loddon Campaspe Irrigation Region (LCIR).’ The Collective not only is proposed to support our own sustainable agricultural practices, but also a dozen other local sustainable farms, and deepen all of our sustainable practices through reduced emissions.

The Recycling Victoria: A new economy[14] policy and action plan for waste and recycling includes the following priorities:

Invest in priority infrastructure: Victoria will have the right infrastructure to support increased recycling, respond to new bans on waste export and safely manage hazardous waste.

Provide support for local communities and councils: A new Supporting Victorian Communities and Councils program will support regional growth and community connectivity

Reducing business waste: A new Circular Economy Business Innovation Centre will help businesses reduce waste and generate more value with fewer resources.

The Collective’s nose to tail and paddock to paddock approach will minimise potential waste, and recycle nutrients on the farm through the use of the in-vessel composting drum, creating a healthy circular bioeconomy.

Finally, a 2019 report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the UN Committee on World Food Security, Agroecological and other innovative approaches for sustainable agriculture and food systems that enhance food security and nutrition[15], recommends:

adapting support to encourage local food producers, food enterprises and communities to build recycling systems by supporting the reuse of animal waste, crop residue and food processing waste in forms such as animal feed, compost, biogas and mulch. (p.22)

[1] Grandin, T. 2020. Behavioural Principles of Stockmanship and Abattoir Facility Design, CAB International.

[2] https://www.health.vic.gov.au/water/protecting-water-catchments

[3] Co-products Compendium, MLA, 2009.

[4] https://www.fao.org/agroecology/database/detail/en/c/1457735/

[5] https://www.hepburn.vic.gov.au/files/assets/public/building-amp-planning/documents/c80hepb-panel-report.pdf

[6] https://www.hepburn.vic.gov.au/Planning-building/Strategic-planning/Hepburn-Planning-Scheme

[7] https://www.planning.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0028/8497/35_07-Farming-Zone-Greyhound-consultation-August-2016.pdf

[8] https://hepburnznet.org.au/

[9] https://participate.hepburn.vic.gov.au/sustainable-hepburn

[10] https://agriculture.vic.gov.au/about/agriculture-strategy

[11] https://agriculture.vic.gov.au/livestock-and-animals/animal-welfare-victoria/animal-welfare/animal-welfare-action-plan

[12] https://www.nccma.vic.gov.au/resources/publications/north-central-victoria-regional-sustainable-agriculture-strategy

[13] https://www.nccma.vic.gov.au/north-central-regional-catchment-strategy

[14] https://www.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-02/Recycling%20Victoria%20A%20new%20economy.pdf

Just over 11 years ago, a wide-eyed young family arrived on Dja Dja Wurrung Country - at 129 Morgantis Road Eganstown – ready to save the world while savouring it. Expressed with a bit less hubris, we just really wanted to enjoy a new life raising animals without fear or pain and able to express their natural behaviours on healthy pastures before taking their lives for human sustenance. Stuart was leaving a decade of middle management in automation with the extreme delight of a wage slave set free with land, sheds, and tools to work on a million projects, and I was armed with a bucketload of cultural theory around consumption and food systems, great admin skills, and no idea where the loin was on a pig or cattle carcass. Neither of us had a clue how to build a fence.

We knew how little we knew, but didn’t know what we didn’t know.

What started as a lifelong concern of mine for how animals are treated in industrial food production has become a complex and skin-tingling ability to see and feel webs of existence that eluded us in our city lives. Learning about grasses has taught us more about soils, and soils have taught us about fungi. Learning about microbial soil fauna has helped us think about the flora reliant on them, which has led us back above ground to native bees, beetles, and the birds that feast on them. Milking Clarabel and Wynny led us to the alchemy of transforming milk into cheese with the help of our tiny friends - lactic acid bacteria - where we encountered once again as if for the first time knowledge gained from a decade of annual traditions fermenting salami, and the summer harvests of garlic, chili, cabbage, and any other vegetable our curious hands can transform into jars of delicious condiments that litter our table and nourish our guts.

Today, we live, farm, feel, and listen on and to Dja Dja Wurrung Country (djandak), and acknowledge the care and custodianship of her First Peoples - Djaara. We pay our deepest respects and thanks for how life here was and continues to be sustained through dhelkunya dja – making good country / making country healthy - and commit our support in returning Country and all her denizens back to health.

We aim to contribute to Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination through land restitution, paying the rent, and decolonial approaches to agriculture.

Long-time followers of the Jonai journey will know that soon after our foray into farming, we built a boning room and commercial kitchen to realise the full benefit of the value chain here on the farm, and I became a vegetarian-turned-pig-farmer-turned-butcher. Many years on from that milestone, we move into 2023 with a focused gaze and a Gantt chart with a timeline for construction on a Jonai Meatsmith Collective abattoir, the development of an agroforestry system integrated into the design around the abattoir, and renewed commitment to the daily practices of farming and living in harmony with nature.

Long host to and members of a dynamic community on and around the farm, in 2023 we welcome the arrival of more careful custodians of Country as Tumpinyeri Growers move their market garden enterprise here in a landsharing arrangement designed to benefit djandak and all she supports.

Jonai Farms and Tumpinyeri Growers will share land, resources, labour, and community to run our respective enterprises raising pastured pigs and cattle and small-scale market gardening. We value relationships over transactions, and reflect on our relationships with djandak to help guide our relationships with each other, other farmers and suppliers, and the communities we feed.

The agreement includes landsharing for farming and also for living. The principles are based on exchanges of various kinds of value - social, ecological, economic, and cultural - where all parties aim to provide and receive value commensurate with need. We acknowledge the privilege we Jonai have in ‘owning’ title to unceded land, and seek through a landsharing agreement and in our daily practices to break down imbalances in power or fairness in our relations with each other and with djandak.

To say we’re excited about what 2023 holds for us and our community is an understatement. I have long described myself as an active optimist – active in my own optimism – and after enduring the biodiversity summit – COP15 – in Montreal last month I suffered a blow to that optimism in spite of my and many others’ activism there. I returned to the healing embrace of djandak and the nourishing interdependencies I have with her denizens, and I remembered I’m not only an active optimist, I’m a fiercely active optimist ever more committed to growing a world where everyone can experience food sovereignty, where Country and First Peoples are acknowledged and their rights to self-determination are respected and promoted.

As we move into this growing collaboration between djandak, Jonai and Tumpinyeri, we’ll share our efforts and our learning in the spirit of the nascent ‘agroecology lighthouse’ movement, ‘from which agroecological principles and lessons radiate out to the broader rural communities, helping them to build the basis of an agricultural strategy that promotes efficiency, diversity, synergy, and resiliency’ (Nicholls & Altieri 2018).

And remember, agroecology is a science, a set of practices, and crucially, it is also a social movement. Its success as a movement depends on the active collectivisation at farm, landscape, community, and national and global social solidarity movements. Wherever you see your opportunities to contribute to this critical transformation of our food and agriculture systems, we hope you act on them! Every person who joins a grassroots democratically constituted organisation like the Australian Food Sovereignty Alliance (AFSA) lends strength in both voice to government and funding for our domestic activities (and you can join for as little as $75 per year!).

Viva 2023! <3

We started talking about the need for small-scale regional abattoirs shortly after we started farming pigs and cattle in 2011, but building a boning room was the immediate priority as we struggled to find regular butchery from the beginning. After commissioning the boning room in January 2014 and the commercial kitchen in July 2015, we forsook industrial grain supplies for the pigs’ feed, shifting entirely to waste stream by the end of 2016. Each of these moves steadily reduced our reliance on commodity supply chains, bringing control of our resource base onto the farm one link at a time.

Our last tie to industrial food systems (aside from diverting their so-called waste from landfill and into the tummies of hungry piggehs) is slaughter. While there are no obvious financial savings to us in building a small facility that can’t lean on economies of scale, the value to us in improved welfare for the animals on their last day is priceless. And of course, like smallholders around the world, we recognize the risk to our entire system should we lose access to the large-scale abattoirs we currently use. This risk is made all the greater by extreme centralisation, which recently got worse with the acquisition of our pig abattoir by the world’s biggest meatpacker JBS, who incidentally were the most affected in the meat industry globally by covid shutdowns.

After years of research on small-scale on-farm and regional abattoirs in the US and Australia, we have settled on a vision to build a micro-abattoir here at Jonai Farms. But unlike building a boning room or kitchen in a quick six-month conversion of a 40-foot refrigerated container, an abattoir is a much bigger undertaking, physically, legislatively, and financially.

We currently butcher with and for seven other farms, and there are several more interested in collaborating if we build an abattoir and bigger boning room and chiller capacity. The existing boning room and commercial kitchen facilities have served us well for the past eight years, but we are at capacity in terms of providing services for others. We are therefore building a new boning room, kitchen and farm gate shop alongside the abattoir to accommodate up to a cap of about 15 farms’ needs.

We are engaged in deeper relationships of reciprocity and mutual aid with these and other farms in collectively solving problems, deepening our knowledge of agroecology, sourcing feed, and sharing occasional labour. The other farmers’ access to our facilities is provided at cost – provision of processing facilities is not how we earn our livelihood, it’s how we ensure more farmers can earn a right livelihood themselves.

We envision the Jonai Meatsmith Collective will be owned and operated by Jonai Farms, but will function as ‘community-supported slaughter’ (CSS) in a similar way to community-supported agriculture (CSA). And like the boning room hire, slaughter will be offered at cost. Farms will sign up as members of the Collective and pay a percentage of their anticipated slaughter fees for the year ahead up front to secure a year of monthly slaughter. While Jonai Farms will employ staff who will coordinate scheduling and manage logistics and communications with members, there will be opportunities for farmers to collectively discuss their needs and negotiate schedules that will accommodate all members fairly and efficiently.

Each year, members will be invited to attend an Annual General Meeting (AGM), where a Profit & Loss (P&L) and Budget will be presented, enabling everyone to democratically set pricing for slaughter to ensure: a viable and resilient meat processing facility, the highest standards of animal welfare, financially sustainable slaughter for members, and fair wages for all staff.

Funding is a critical piece of the puzzle – just as we eschew external inputs at our farm, we are committed to avoiding debt to build infrastructure. Debt avoidance is pivotal to degrowth thinking and doing. The interest we would have to repay – profits to the bank’s shareholders – would seriously undermine our capacity to build and operate a viable abattoir. In addition to our savings, a creative combination of offering some enticing rewards such as Tammi’s upcoming cookbook (!), Speckleline hides, and in person fundraising, with the possibility of some grant money, will be used to raise the funds we need to build the facility, and as you’ll read below, we’ll be accepting donations as well. We've also been supported by the excellent young agrarians, who raised 16 of our surplus pigs, and have butchered and sold the pork independently to kick off our fundraising. The business model will be self-sustaining, and reliant on its not-for-profit approach.

Our current budget estimates are coming in between $400k and $500k. There are a lot of unknowns in an owner-built facility that will be functional and durable, environmentally sustainable with very high animal welfare standards for lairage and stunning, and aesthetically pleasing for workers and visitors alike, using a combination of new and secondhand materials as appropriate to all of these values. There are no ‘out of the box’ solutions for context specific problems, no matter how much industrial society wants you to think there are.

For many years we have been working to build diversity and resilience on the farm – from biodiversity through to diverse skillsets amongst our team. With the abattoir addition, our aim is to enable all of us to be able to work across the system – farming, slaughtering, butchering, and delivering – as well as maintaining a regular spot on the lunch roster. As we’ll be processing for several other farms, there will be plenty of work to go around! Jonai Farms already functions as a farmer incubator, and adding an abattoir will mean the opportunity to teach whole value chain skills to grow a future generation of farmers and farm and food workers. Tammi and lead farmhand Adam are currently nearing completion of their meat inspector training – another piece of the puzzle solved.

The following is our proposed timeline, subject to all the caveats of things beyond our control, such as Council planning timelines, supply chain disruptions due to the pandemic and the war in Ukraine, Stuart’s and other workers’ availability, other farm demands, funding, and the weather.

Timeline

Oct 2021- Jun 2022

Project planning phase

· Development of vision and project plan

· Abattoir design

· Draft budget

· Preparation of Development Application

· Funding model development for capital expenses

· Business modelling

Apr 2022

Commence fundraising

Jun 2022

Submit Development Application to Council

Nov-Dec 2022

Site preparation & start ordering equipment

Jan 2023

Commence construction

Oct 2023

Commission facility, including license with Primesafe

De-commission and sell existing facilities

As always at Jonai, we remain committed to radical transparency. As we progress this project, we will share our learnings with you for better or worse, and we will make all of our documentation freely available.

We have always shared what we learn, and we will continue to do so, but in the interest of raising the funds for the project, we have decided to accept donations from any who might like and be able to provide a bit of support for our efforts to radically transform the food system from the ground up. Unlike in capitalist society generally, the ability to pay will NOT provide privileged access to the knowledge we are sharing, but rather will ensure that it is shared with everyone.

Imagine if our communities all around Australia and the world pooled our resources in this way to reclaim control of the means of production, and the means of communication, energy, transport – the sky’s the limit!

Viva!