Seven years ago today we scraped up Morgantis Road in a low-slung Volvo bursting with the high-pitched voices of our gaggle of excited small children and a brand-new shiny green wheelbarrow strapped to the roof.

A decades-long desire to live on the land was at last being realized. I remember the first year of corporeally re-inhabiting the rural life – striding across paddocks, shifting gears to make it over the crest to the next horizon, wearing whatever crazy mixed ensemble I’d wrapped pragmatically around my form that morning on a quick run to town, lucky I remembered to change out of my slippers and into elastic-sided work boots. This was my childhood, renewed and transformed.

Just 15 months earlier we had listened to Joel Salatin speak at the Lake House in Daylesford and I’d turned to my beloved Stuart, slapped him on the leg, and said, ‘that’s it! We’re going to be farmers!’

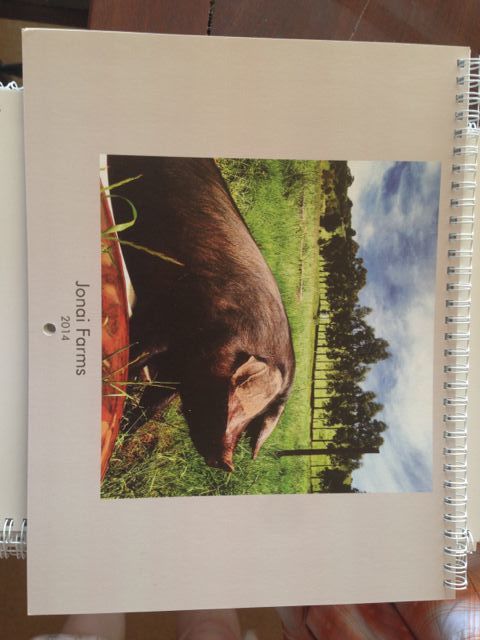

The first year was a rose-tinted dream, a rural idyll, in which we climbed the volcano for the views instead of to find a short in the fence, and had such poor priorities that the next year would see us scrambling to fence ahead of a quickly growing herd of beautiful Large Black pigs.

Stuart took to the farm like the Mr Project Man he’d always been, with a brand new giant shed we thought would take years to fill but that in fact was full in a sparrow’s heartbeat. His first project was to build us a bedroom from the shipping container that had carried our mountains of lifestuff up to the farm. It was the first of many such container conversions at Jonai!

After waiting a few months for our first tiny herd of five gilts and a boar, the first litter of tiny little black piglets were born to Keen in June 2012, and Big Mama a fortnight later, and we learned a hard lesson about the importance of colostrum for newborns that confirmed what I’d advocated for human babies in my early years of mothering.

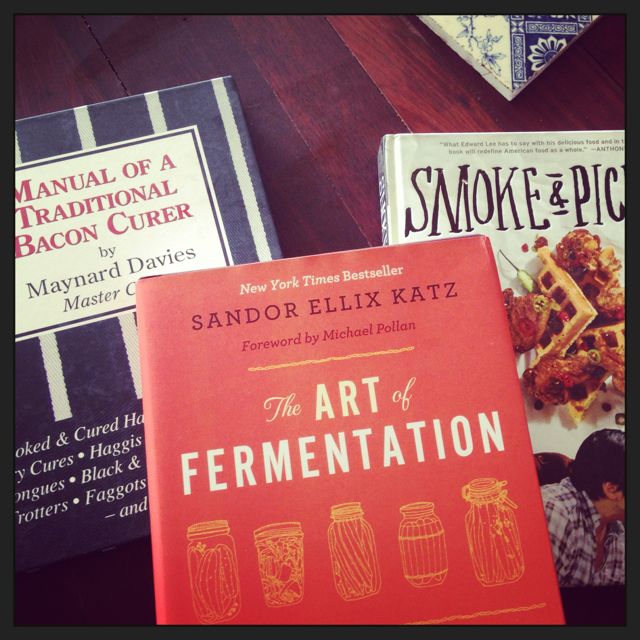

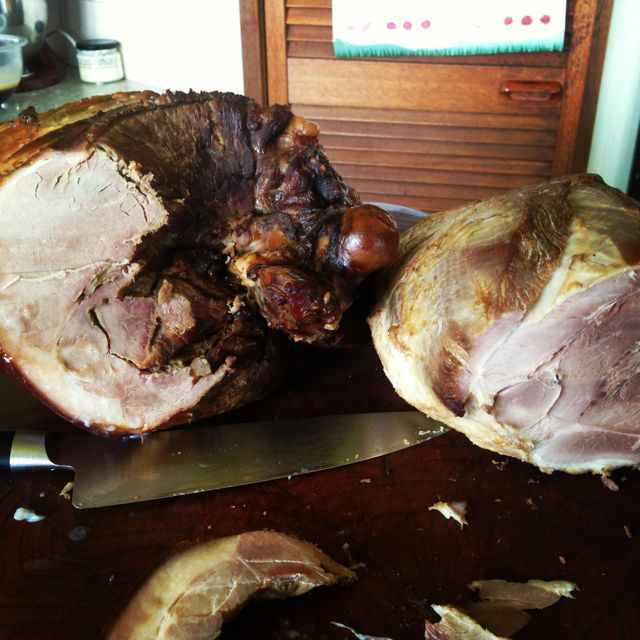

Nearing Christmas that year we started to approach local butchers to cut our first pig with all the ignorance of newbies to the meat industry. Lesson One: don’t talk to butchers about anything, but especially not ham, in the weeks before Christmas! We had our first pig slaughtered, and after collecting the carcass, Stuart picked me up from the train station at the end of a week working in the city for the federal government (what was I thinking?!). At about 7pm I commenced butchering my first pig with nothing but a couple of books and youtube on my side. A butcher was born.

After all the local butchers turned us down when we asked about contract butchery for smallholders, we found the wonderful Sal of Salvatore Regional Butchers about half an hour away in Ballan. Sal not only agreed to cut our pigs for us (two per fortnight at that stage), he also was just mad enough to agree to teach me butchery while he did it. By the time he agreed, we’d already decided we would build our own boning room, and that the way to do it was to crowdfund it.

In 2013 we raised $27,500 to build our boning room, and while Stuart built it, I learned pork butchery with Sal. Two pigs a fortnight was all we were doing in those early days, a tough way to learn butchery with so little repetition and two weeks between cutting sessions. And for the life of me I can’t remember why I didn’t do more than one session watching Sal cut our beef… leaving me to work out how to do it. In my first year I had a beautiful elderly local customer bring back a piece of meat to gently say, ‘I think you’ve just cut a bit too far along and got yourself into the round, dear.’

I ran our first butchery demo workshop during the DMP Harvest Festival out on the back patio, showing some 50 people how to cut up a pig on what was my sixth ever carcass while my helpful father-in-law stood heckling me from the back. I got a quick lesson in catering for large numbers in preparation for that day, and have never done potatoes gratin for 50 since.

While we were crowdfunding the boning room, we also went on ABC Bush Telegraph for a six-month stint following one of our piglets from paddock to plate. With all the naïve wisdom of people who’d been farming five minutes, we agreed to ask the public their views on our management systems, starting with castration. We’d only just begun to think we would start castrating after some unwanted teen pregnancies and a couple of instances of boar taint in the meat, after an initial resistance to the idea as an ‘unnecessary intervention’. The vegan abolitionists castigated us for it, swiftly thickening our skin but also cementing our commitment to radical transparency on the farm.

In January 2014, just over two years after we arrived in Eganstown and one year selling meat, the boning room was licensed by PrimeSafe and we launched our first CSA shares. That year is a blur to me of cutting, new muscles and sore heels, help from friends, making new friends in the good folks who started turning up to volunteer because they just liked the cut of our jib and wanted to contribute to something exciting (I’m looking especially at you, Jass, my first ever meat grrl, then Head Meat Grrl, and forever meat grrl, friend, and comrade in arms), and hours of Fat Freddy’s Drop, Milky Chance, and country AND western music just like my mama. #meatgrrlsmonday for lyf! That’s the year we also became profitable after just two years (instead of the projected five) and we haven’t looked back.

We ran our first Salami Days – teaching people the age-old art of meat, salt, & time. We butchered, seasoned, minced, and stuffed many kilos of salami and hung them in the shed to be enjoyed in a few months’ time. And then PrimeSafe came and destroyed them all. Another hard lesson was learned about the state of food safety regulations in this country, galvanizing me to start garnering stories and evidence for a campaign to change things… by this time I was President of the Australian Food Sovereignty Alliance (AFSA), so I not only had the collective to work with, I had a framework to understand clearly what’s at stake, what we’re fighting for, and who we’re up against.

A year on we rounded up another successful crowdfunding campaign and by 2015 I had a commercial kitchen and curing room to play in, thanks to Stuart’s mad skills in converting containers to incredibly useful workspaces. The new space took us from paddock to plate to paddock to paddock, as we utilize every part of the carcasses – heads are paté de tête or guanciale, pork cheeks, and ears are dehydrated for pet treats, as are trotters; and a quarter of the bones become bone broth and three quarters go to the members. After making paté or bone broth, the spent bones go out to Stuart’s retort to be pyrolised into bonechar – a mineral-rich form of activated carbon that does wonders for our tiny commercial garlic crop and the home garden.

As we increased production of more value-added products on the farm, I also stepped up the advocacy with AFSA as we worked towards establishing a Legal Defence Fund to support farmers against the tyranny of rogue regulators, and scale-inappropriate regulation and land use legislation. Speaking truth to power, demanding the same accountability from government that they demand from food producers, AFSA started gaining real ground as representatives of key stakeholders in the food system – small-scale regenerative farmers.

But all this advocacy meant I took my eye off the ball and the farm suffered for it. Stuart was carrying too much of the load on his strapping shoulders, and we sailed into a fertility crisis that would see us lose nearly 40% of our pork production due to small or non-existent litters as our herd aged, the weather heated unseasonably early, and many of the sows simply got a bit too fat. 2016 was a really tough year.

With the generous support of our beautiful CSA members, we scraped through that year. Great disruptions are known to cause innovation, and after careful planning, we renounced all purpose-grown commercial grain from the pigs’ diet by December, cutting nearly $20,000 out of our annual costs. Contrary to industrial ag wisdom, an ecologically-sound improvement to our model was also an excellent financial decision for the farm. Giving up grain grown in monocrops reliant on petrochemical inputs to instead divert hundreds of tonnes of food waste from landfill was a deeply satisfying shift that furthered our efforts to be a truly agroecological farm.

February 2017 was a major milestone for the Jonai, as Joel Salatin, the man who inspired us to farm in the first place, joined us on the farm along with long-time AFSA champion Costa of ABC Gardening fame, for a fundraising event for the brand new AFSA Legal Defence Fund, raising $35,000 on the day and growing awareness of the challenges small-scale farmers are facing in scale-inappropriate and poorly rationalised legislation.

One milestone often drives another, and this one brought a team of volunteers who enthusiastically helped Stuart finish the Belvedere, our magnificent events shed built entirely of secondhand materials, largely windows. A feeling of completeness accompanied the rustic chic of the Belvedere, making workshops such a breeze to run with the long table for lunch waiting prettily while we butcher and craft salami in the middle of the space, but it wasn’t long before there was an itch…

And so Stuart has commenced building a back kitchen and cellar on the back of the Belvedere to make workshops easier to cater and give us a spot for our salami and cheese curing, beer making, and preserve storing… plus a pizza oven is in the works to take centre stage in the Belvedere, and Stuart’s feed shed out back just needs its roof… and of course we’re keen for a bit more short-term accommodation for the flow of beautiful people who grace our patch of dirt through all seasons, and Stuart just registered Wasted Distillers…

And there’s always the entire food and agriculture system to transform to keep me busy. ;-)

Viva la revolución! Viva la via campesina!

From February onwards, Sal let me cut with him each fortnight when we sent him our pigs, which was incredibly generous considering I slowed him down to about quarter speed. He was a good-humoured taskmaster, teaching me how to cut my bellies straight, where to find the joint on the shoulder, and to waste nothing, as well as how to stop waving my boning knife around in a rather alarming fashion. He makes quality sausages too, which were certainly well received by our earliest Jonai Farms community of eaters!

From February onwards, Sal let me cut with him each fortnight when we sent him our pigs, which was incredibly generous considering I slowed him down to about quarter speed. He was a good-humoured taskmaster, teaching me how to cut my bellies straight, where to find the joint on the shoulder, and to waste nothing, as well as how to stop waving my boning knife around in a rather alarming fashion. He makes quality sausages too, which were certainly well received by our earliest Jonai Farms community of eaters!